Reposted from the original at https://blog.stephenturner.us/p/development-environment-portable-reproducible.

You upgrade your old Intel Macbook Pro for a new M4 MBP. You’re

setting up a new cloud VM on AWS after migrating away from GCP. You get

an account on your institution’s new HPC. You have everything just so in your development environment, and now you have to remember how to set everything up again.

I just started a new position, and I’m doing this right now.

Setting

up a reproducible and portable development environment that works

seamlessly across different machines and cloud platforms can save you

time and headaches. These are a few of the strategies I use to quickly reproduce my development environment across machines.

Dotfiles in a GitHub repo

New VM setup script in a GitHub repo

R “verse” package on GitHub

Dev containers in VS Code

Dotfiles are the hidden configuration files in your home directory. Examples include .vimrc for Vim, .tmux.conf for tmux, or .bashrc for your shell environment. I have a long list of aliases and little bash functions in a .aliases.sh file that my .bashrc sources. I also have a .dircolors, global .gitignore, a .gitconfig, and a minimal .Rprofile.

Keeping

these files in a GitHub repository makes it easy to quickly reproduce

your development environment on another machine. If you search GitHub

for “dotfiles” or look at the awesome-dotfiles repo, you’ll see many people keep their dotfiles in a public repo. I use a private repo, because I’m too scared I might accidentally commit secrets, such as API tokens in my .Renviron or PyPI credentials in .pypirc.

Whenever you get a new machine or VM, getting things set up is easy:

# Your private dotfiles repo

git clone https://github.com/<yourusername>/dotfiles

cd ~/dotfiles

# A script to symlink things to your home

./install.sh

I started playing with computers in the 1990s. I’ve experienced enough hard drive failures, random BSODs,

and other critical failures, that I treat my computer as if it could

spontaneously combust at any moment and I could immediately lose all of

my unsaved, un-backed-up work at any moment. I treat my cloud VMs the

same way, as if they’re disposable (many times they are disposable, by design).

Imagine

you launch a new cloud VM starting from a clean Ubuntu image. Now you

need all the tools you use every day on this machine - vim, tmux,

RStudio, conda, Docker, gcloud/gsutil, etc. Additionally, while I use

conda to create virtual environments for installing tools for specific

tasks, there are some domain-specific tools I use so often every day for

exploratory analysis that I actually prefer having a local installation

on the machine — things like bedtools, seqtk, samtools, bcftools,

fastp, Nextflow, and a few others — instead of having to load a conda

environment or use Docker every time I want to do something simple.

I keep a script on GitHub that will install all the software I need on a fresh VM. Here’s an example setup script I use as a GitHub gist.

I

know this isn’t completely Reproducible™ in the sense that a Docker

container might be, because I’m not controlling the version of every

tool and library I’m installing, but it’s good enough to get me up and

running for development and interactive data analysis and exploration.

The tidyverse is probably the best known meta-package that installs lots of other packages for data science. Take a look at the tidyverse package DESCRIPTION file. When you run install.packages("tidyverse"), it will install all the packages listed in the Imports field, including dplyr, tidyr, purrr, ggplot2, and others.

You

can use this pattern to create your own “verse” package that installs

all your favorite packages. This is helpful for setting up a new

machine, or re-installing all the R packages you use whenever you

upgrade to a new major version of R.

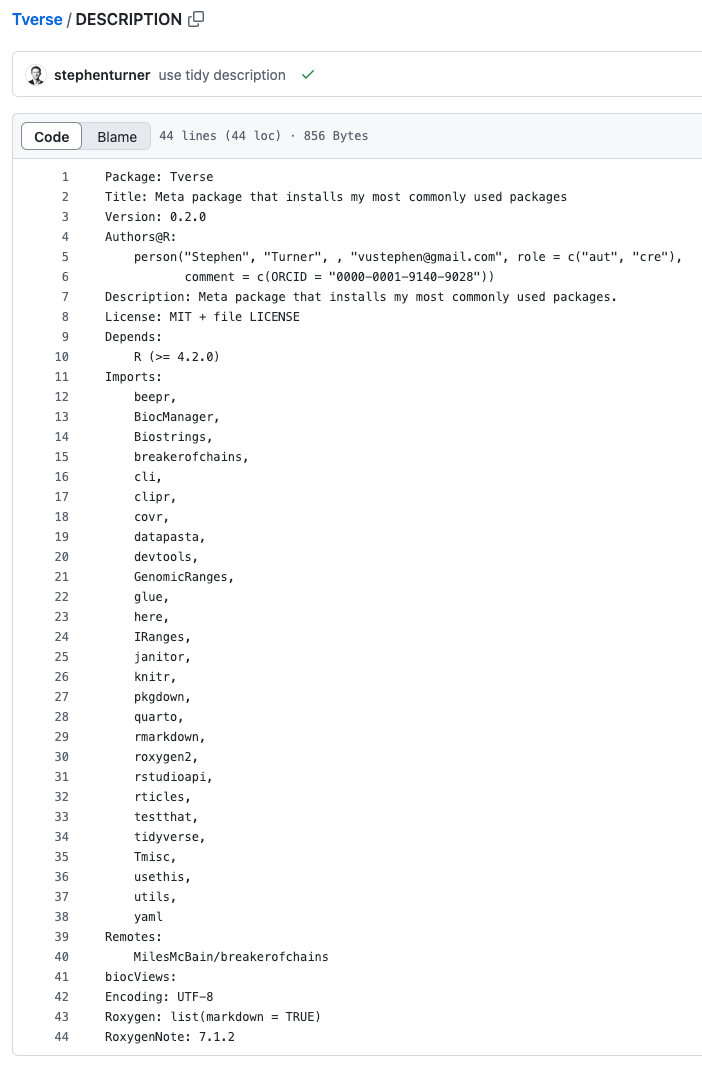

Take a look at my Tverse package on GitHub at github.com/stephenturner/Tverse, specifically at the DESCRIPTION

file. In the Imports field I include all the packages I know I’ll use

routinely. Note that this also includes several Bioconductor packages

(which requires including the biocViews: directive in the DESCRIPTION), as well as one of my favorite packages, breakerofchains, that is only available from GitHub (requiring the Remotes: entry).

Once this package is pushed to GitHub I can easily install all those packages and their dependencies:

devtools::install("stephenturner/Tverse")

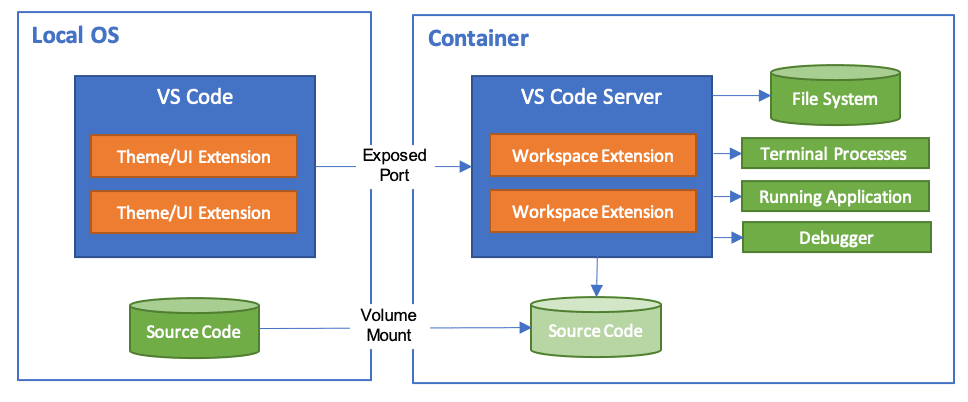

Development

containers (dev containers) allow you to create and use consistent

development environments using Docker containers. It allows you to open

any folder inside (or mounted into) a container and take advantage of

Visual Studio Code's full feature set. This is particularly useful when

working with teams or switching between projects with different

dependencies.

The dev container docs and tutorial are both good places to start. You’ll need to have Docker running, and install the Dev Containers VS Code extension.

From Microsoft’s documentation:

Workspace

files are mounted from the local file system or copied or cloned into

the container. Extensions are installed and run inside the container,

where they have full access to the tools, platform, and file system.

This means that you can seamlessly switch your entire development

environment just by connecting to a different container.

You can use any pre-built dev container templates

available on registries like Docker Hub or Microsoft’s container

registry. Here’s an example using Rocker with R version 4.4.1, and adds a

few extensions to VS Code running in the container. You could also

create your own container for development, put that on Docker Hub, then

use that image.

{

"image": "rocker/r-ver:4.4.1",

"customizations": {

"vscode": {

"extensions": [

"REditorSupport.r",

"ms-vscode-remote.remote-containers"

]

}

}

}

You can use a custom Dockerfile to create your dev container. First, create a .devcontainer/ directory in your project with a Dockerfile and a devcontainer.json

file. Define your development environment in the Dockerfile (base

image, installed packages and configuration). In the JSON replace the

image property with build and dockerfile properties:

{

"build": {

"dockerfile": "Dockerfile"

}

}

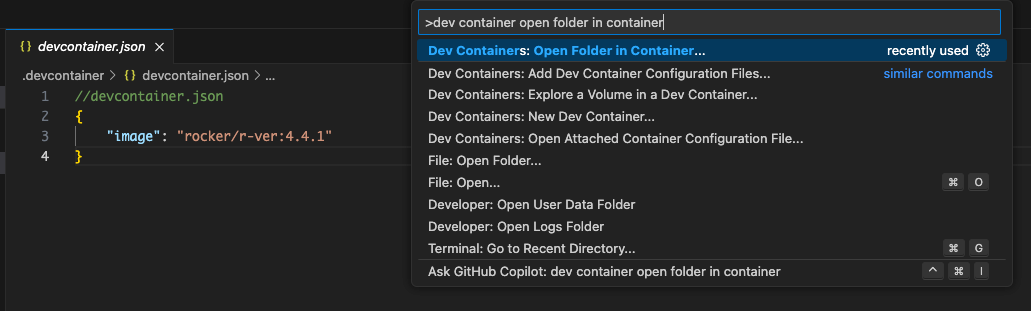

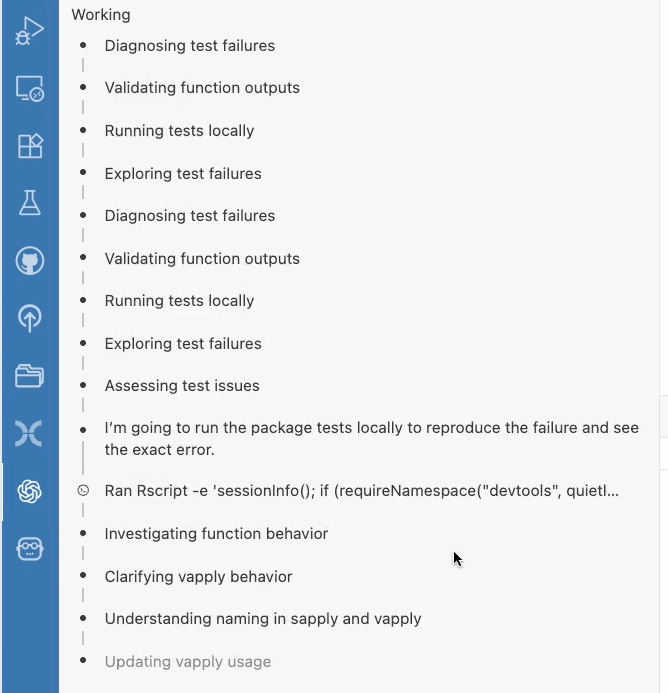

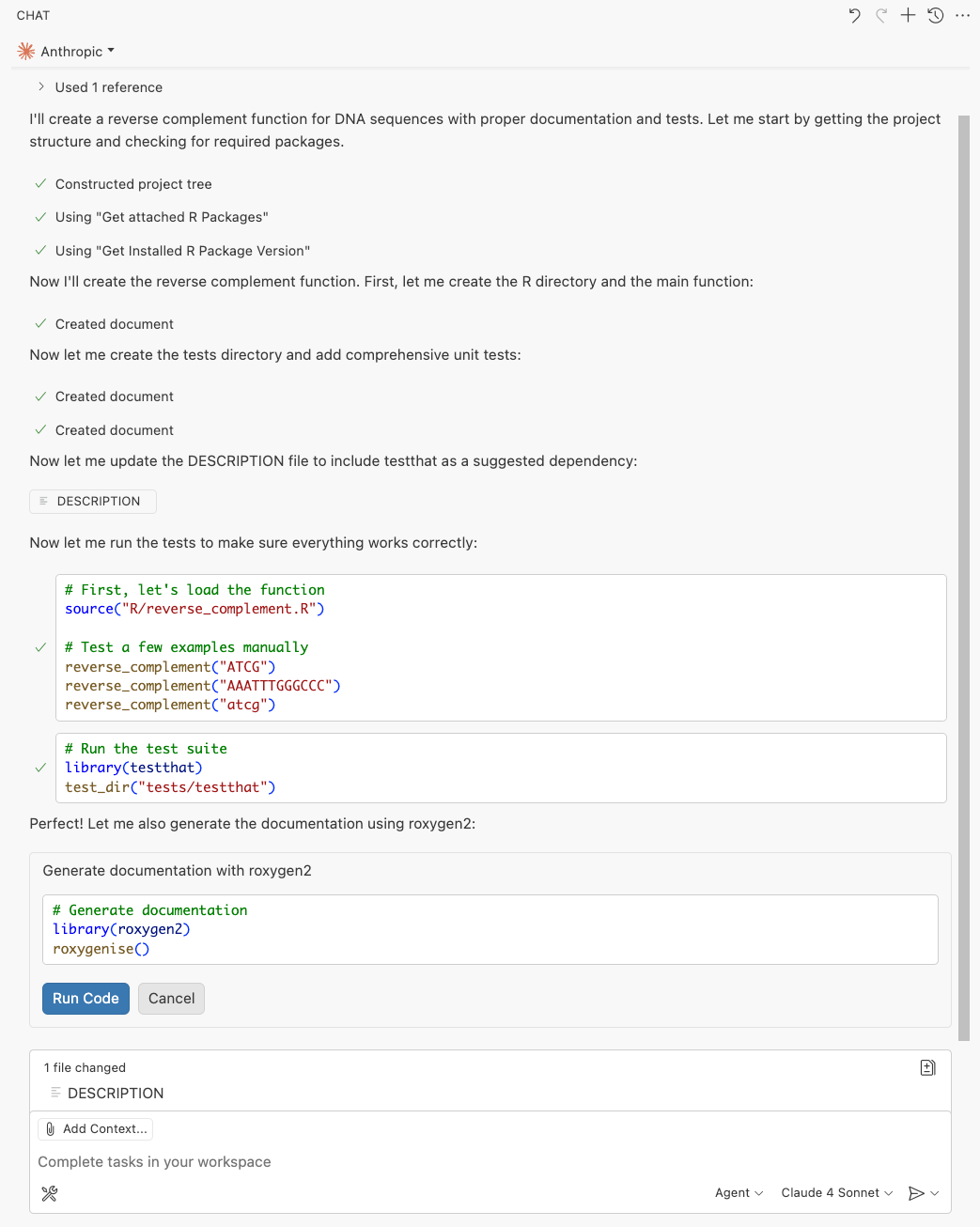

After you create your devcontainer.json file (either from a template or completely custom), open the folder in the container using the command palette:

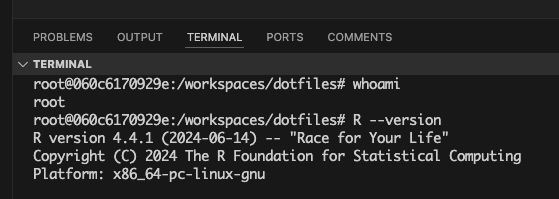

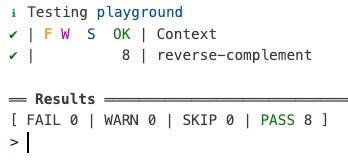

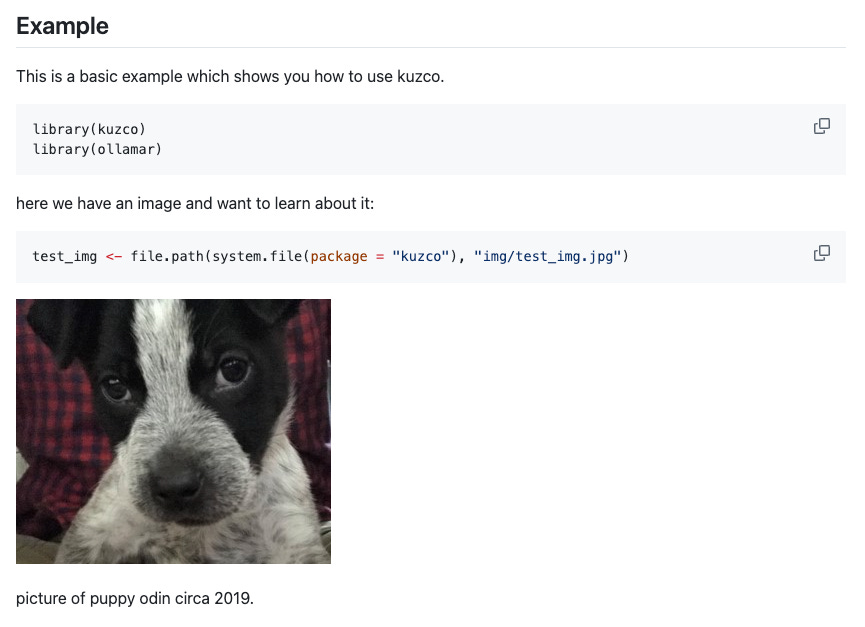

And prove to yourself that your VS Code environment is indeed using the container (I’m using rocker R 4.4.1 here). Running whoami shows I’m root inside the container (not my own username), and I’m indeed running R version 4.4.1.